In the early months of 1916 the Great War was well into its second year and the news from the front was far from encouraging. With stalemate in France attention had turned to the Mediterranean and the Near East. The mood was extremely gloomy with the last troops being evacuated from the Dardanelles and the siege of the British garrison in Kut. Yet few could have foreseen that, within months, all eyes would be on events in Dublin with the dramatic news of an armed rebellion against British rule and the declaration of an independent Irish Republic on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916.

The Easter Rising was reported by a 16 year old Cardiff soldier, Ernest Edward Thomas, serving with the 3rd Welsh Horse in Dublin. Ernest was the son of a fruit and flower merchant, originally from St Issells, Pembrokeshire, also called Ernest Edward. The family lived at 288 Newport Road, Cardiff and Ernest had attended Marlborough Road School before moving on to the Cardiff Municipal Secondary School at Howard Gardens in 1912. The school was referred to by pupils as the MSS and, along with many other former pupils, Ernest wrote to his former head teacher, William Dyche, about his war time experiences. William Dyche retained the letters received in 1914-16 and they are held at Glamorgan Archives. The letters provide first-hand accounts of service in the armed forces in World War 1, from basic training through to life at the front in just about every theatre of war.

It might have been thought that a posting to Dublin would be far removed from the thick of the fighting that had spread from France to fronts across Europe, the Mediterranean, the Near East and Africa. It appeared that the British had not anticipated significant unrest in Dublin in April 1916 given that only a thousand troops were stationed in the city. The British forces included several cavalry units and Ernest Thomas was attached to the Welsh Horse based at the Marlborough Barracks in Dublin. Although only 16 years of age Ernest was in the thick of the action from the outset. The Welsh Horse was one of the first units to be summoned from Barracks on Easter Monday and in two letters to William Dyche, dated 12th and 18th May, Ernest provided a first-hand account of the rising.

Ernest Thomas described the rising as ‘…a very unexpected affair so far as we were concerned’. So much so that on the morning of 24 April he was playing ‘footer’ when the alarm was sounded.

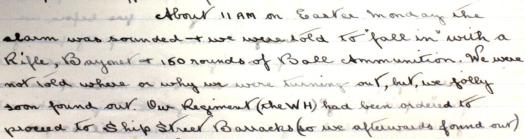

About 11 a.m. on Easter Monday the alarm was sounded and we were told to ‘fall in’ with a rifle, bayonet and 150 rounds of Ball Ammunition. We were not told where or why we were turning out, but, we jolly soon found out. Our Regiment (the W H) had been ordered to proceed to Ship Street Barracks (so we afterwards found out) [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

The alarm was a result of the news that armed Irish Republicans led by James Connolly had occupied a number of key buildings in Dublin including the Post Office, the Four Courts, Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, St Stephen’ Green and Dublin City Hall. There had also been attempts to capture Dublin Castle and Trinity College. Following the capture of the Post Office, Patrick Pearse had proclaimed an Irish Republic and a Republican flag had been raised. In all, the Republican Forces in Dublin drew together around 1200 men, primarily from two groups, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizens Army.

In previous months the authorities had been aware of preparations for a rising against British control of Ireland. Yet little had been done to prepare for the events of April 1916. It is possible that the interception by the Royal Navy of a German ship carrying arms for the rebels had persuaded the British authorities that planning for an uprising had been badly dented. If so, they seriously underestimated the resolve of the Republican movement.

The Welsh soldiers would have had very little idea of what they were likely to face on the morning of Easter Monday as they left Marlborough Barracks. Few could have anticipated, or been prepared for, the events of the following seven days.

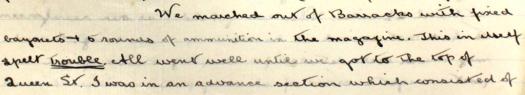

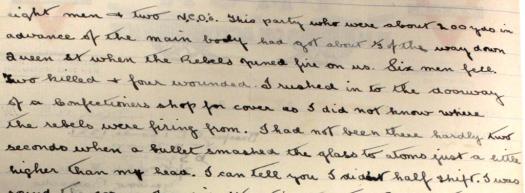

We marched out of Barracks with fixed bayonets and rounds of ammunition in the magazine. This in itself spelt trouble. All went well until we got to the top of Queen St. I was in an advance station which consisted of eight men and two N.C.Os. This party who were about 200 yards in advance of the main body had got about a third of the way down Queen St when the rebels opened fire on us. Six men fell. Two killed and four wounded. I rushed into the doorway of a confectioners shop for cover as I did not know where the rebels were firing from. I had not been there hardly two seconds when a bullet smashed the glass to atoms just a little higher than my head. I can tell you I didn’t half shift [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

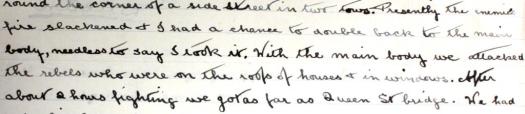

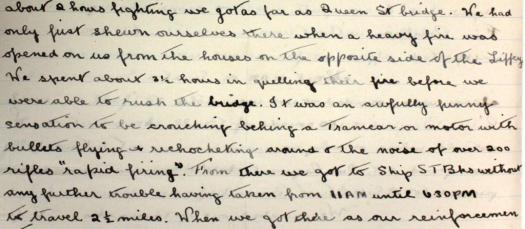

Presently the enemies fire slackened and I had the chance to double back to the main body, needless to say I took it. With the main body we attacked the rebels who were on the roofs of houses and in windows. After about 2 hours fighting we got as far as Queen St Bridge [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

Marlborough Barracks was on the north side of Dublin. The Welsh Horse were moving to the centre of the City and ever closer to the key areas and buildings held by the Republicans. As might be expected they quickly ran into a hail of rifle fire. Ernest’s account, as a very young soldier experiencing action for the first time, was remarkably collected. However, at times there were hints of the confusion and fear that he must have felt

The rebels were on the house-tops (three quarters of the houses in Dublin have flat roofs) and in the windows, in fact they were firing from everywhere and the worst part of it was we could not see them to fire back….I can tell you honestly that it is not very pleasant to have someone doing a little rifle practice on you [Letter of 12 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

On arrival at the Queen Street Bridge over the River Liffey, in the centre of Dublin, the Welsh Horse found the bridge barricaded and defended. The Republicans had also occupied houses on the opposite bank.

We had only just shown ourselves there when a heavy fire was opened on us from the houses on the opposite side of the Liffey. We spent about 3 ½ hours in quelling their fire before we were able to rush the bridge. It was an awfully funny sensation to be crouching behind a Tramcar or motor with bullets flying and ricocheting around and the noise of over 200 rifles ‘rapid firing’. From there we got to Ship St Bks without any further trouble having taken from 11 am until 6.30pm to travel 2 ½ miles [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

Unprepared for the level of opposition that they had encountered, the British forces in many areas were forced to wait for reinforcements before attempting to dislodge the rebels. The struggle became a war of attrition with both sides trying to extend their control of key parts of the city. For much of the next two days Ernest watched the fighting unfold from the rooftops.

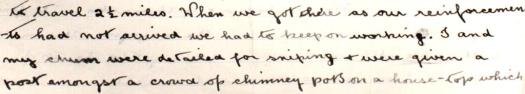

When we got there, as our reinforcements had not arrived we had to keep on working. I and my chum were detailed for sniping and were given a post amongst a crowd of chimney pots on a house-top which we discovered was excellent cover and did some rather decent shooting from there. We were relieved at 4.30pm on Tuesday having been working since 5am Monday without food (except breakfast before leaving Bks Monday) or relief until 4.30pm Tuesday [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

This was to be the pattern for the next week, as Ernest continued to be employed as a sniper moving from building to building. This was a period of bitter fighting with civilians often caught in the crossfire. However, the balance of power was shifting quickly. The British had declared martial law in Dublin and, with the city under the control of the military, British troops, supported by artillery, flowed into the city and soon numbered nearly 16,000 men.

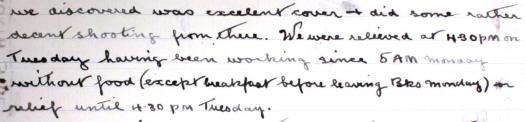

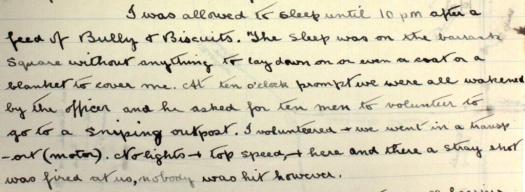

I was allowed to sleep until 10pm after a feed of Bully and biscuits. The sleep was on the barrack square without anything to lay down on or even a coat or a blanket to cover me. At ten o’clock prompt we were all wakened by the officer and he asked for ten men to volunteer to go for a sniping outpost. I volunteered and we went in a transport (motor). No lights and top speed, and here and there a stray shot was fired at us, nobody was hit however [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

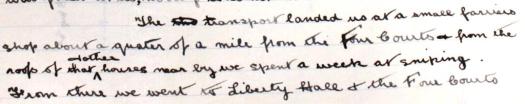

The transport landed us at a small farrier’s shop about a quarter of a mile from the Four Courts and from the roofs of that and other houses nearby we spent a week at sniping. From there we went to Liberty Hall and the Four Courts and from there finally to Jacobs Biscuit factory [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

The above excerpt is taken from Ernest’s second letter dated May 18th. It is clear that he was involved in some of the fiercest fighting at the Four Courts and Jacob’s Biscuit Factory. Yet, in his second letter, he provided little by way of detail. However, in the earlier letter, dated 12 May, he had much more to say about this period. For example, he referred to sniping from the tower of Dublin Castle and having shot a Republican stationed on the roof of the Four Courts. We will never know just how much of this was bravado by a 16 year old. If it was true, he had decided by the time of his second letter to be more circumspect about events in Dublin in April 1916.

One common theme in both letters is his preoccupation with searching for food as the fighting stretched over a number of days. Again he had much more to say about this in his first letter and he talked of taking food from ‘looters’.

We had no food sent through to us. I believe that in the rush we were forgotten, anyhow we did well. Starving ‘men’ are not particular, so seeing some looters passing, we took their loot from them at the point of bayonet and lived like kings on sardines, butter, cake, jam, bacon, eggs, biscuits etc, but we could not get any bread or anything to drink.

I was having ‘dinner’ which consisted of 2lb seed cake, a tin of skipper sardines and a pocketful of all sorts of biscuits and the best chocolate and an old bully tin which was half full of water? (or water with variations such as sardine oil, bits of cheese, cake and biscuits would describe it better) when a bullet flattened itself at my feet almost (I am enclosing part of it, the other bit went west, please give it to my mother afterwards and show her this letter (as I could not write two letters like this and live)). It was an awful nuisance because it made me upset the sardines all over my best breeches, and oil will stain them [Letter of 12 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

Again there was probably an element of bravado in this. He returned to this theme in his second letter but made no mention of looters. It appeared that, after the cessation of hostilities, he was very aware of the hardship and suffering inflicted on the people of Dublin.

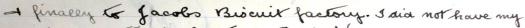

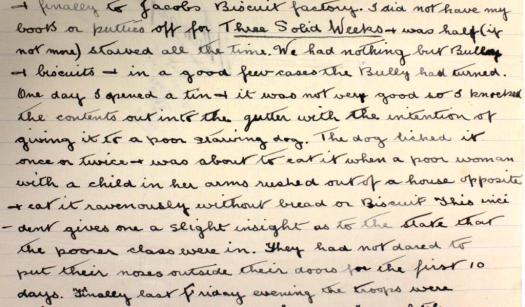

I did not have my boots or puttees off for three solid weeks and was half (if not more) starved at the time. We had nothing but Bully and biscuits and in a good four cases the Bully had turned. One day I opened a tin and it was not very good so I knocked the contents out into the gutter with the intention of giving it to a poor starving dog. The dog licked it once or twice and was about to eat it when a poor woman with a child in her arms rushed out of a house opposite and eat it ravenously without bread or biscuit. This incident gives me a slight insight as to the state that the poorer class were in. They had not dared to put their noses outside their doors for the first 10 days [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

With reinforcements from Britain and the Curragh, supported by artillery, the British Forces were able to steadily gain ground but often at heavy cost. After being forced to abandon the GPO building, Pearse ordered a surrender on Saturday 29 April. Volunteers in other key buildings followed suit the next day. However, for Ernest and the Welsh Horse there was still much to be done to secure key buildings across the city and remove any last points of resistance.

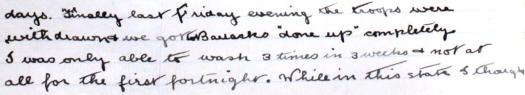

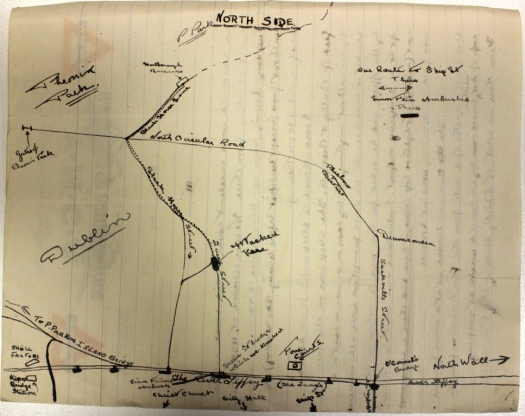

Finally last Friday evening the troops were withdrawn and we got to Barracks ‘done up’ completely. I was only able to wash 3 times in 3 weeks and not at all for the first fortnight. While in this state I thought of a new version to a very popular hym and it suited me to the “T”. Instead of Rock of Ages left for me, it was Muck of Ages grained in me let me rid myself of thee. Well I must close now hoping that the rough scetch which I have enclosed will be of some use [Letter of 18 May 1916, EHGSEC11/55].

The rising was over. It was estimated that 64 members of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizens Army were dead along with 132 British soldiers and police. Sadly, over 250 civilians had also been killed with evidence that both the British Army and the rebels had been responsible for civilian deaths. Following a wave of arrests and court martials, 15 men, including Patrick Pearce and James Connolly, were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad in May as ringleaders of the rising.

With the surrender in Dublin, planned risings in other parts of Ireland, including Cork, faded away. If, however, the British authorities in Dublin thought that they crushed the republican movement they were well wide of the mark. The leaders of the rising were acclaimed as martyrs and within a year many elements of the nationalist movement had come together to form Sinn Fein. Although not apparent at the time, Ernest Thomas and the Welsh Horse had been part of events that only increased the demand for, and the movement towards, the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Tony Peters, Glamorgan Archives Volunteer