The Board of Trade held responsibility for the general superintendence of matters relating to merchant ships and seamen. This included overseeing formal investigations into any shipping casualties on or near the coasts of the United Kingdom and for any British ship, stranded, damaged or lost.

Amongst the records for Cardiff Petty Sessions Court are a series of files relating to such investigations held at Cardiff City Hall and Law Courts during the period 1875-1935 (ref. CL/PSCBO/BT). Composed of papers assembled for the inquiry, depositions of witnesses and accounts of the proceedings of the court, the files represent an invaluable source for maritime history in the 19th and 20th centuries. Often written in pencil and sometimes hard to read, the bundles of papers provide a wealth of information about matters ranging from ship design to ship discipline.

Since the place of investigation was to be the place most convenient for witnesses, by no means all the shipping casualties investigated in Cardiff were Cardiff-based ships. Some of the ships were registered in other ports and have no obvious connection with Cardiff other than regular trade with a South Wales port or a predominance of Welsh names amongst the crew lists. Equally, Cardiff ships were sometimes subject to investigations in other ports, as in the case of the SS Albion of Cardiff, which was owned by the Duffryn Shipping Company of Cardiff and was lost off Spain in 1908. The inquiry into her loss was held at Caxton Hall, Westminster.

Among the earliest papers perhaps the most interesting are those highlighting the hazards involved in carrying dangerous cargoes. In December 1880 explosive gas given off from a cargo of coal was suspected as the cause of the loss of the SS Estepona of Hull whilst she sailed from Cardiff to Marseilles. The case file for the inquiry includes depositions from the owner concerning the ship, her ballast and insurance, the chief accountant to the colliery which supplied the coal, a foreman trimmer who remembered loading the coal and a Government Inspector of Mines for South Wales who advised on the likelihood of explosive gas forming. In this case there was no definite decision about the cause of the loss, but a year later there were more definite conclusions about the SS Penwith of Hayle, which disappeared having left Penarth bound for the Rio Grande. She carried 422 tons of South Wales steam coal, drawn from collieries in the Rhondda and Ogmore valleys. The coal was notorious for the explosive gas it emitted. In his report to the court, the Inspector of Mines outlined the importance of ventilation, since gas was normally given off some days after the coal was wrought, and he criticised the situation whereby the hatches were the only form of ventilation even though these might well have to be closed in bad weather. In concluding that ventilation on the ship was inadequate, the court attributed blame both to the builder and to the master of the ship as well as to the owner.

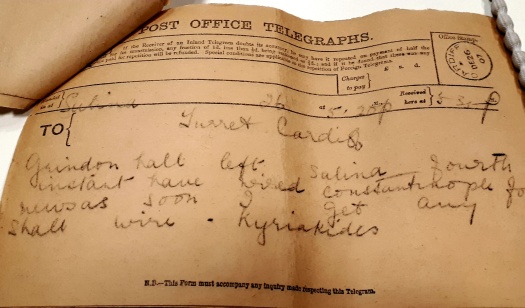

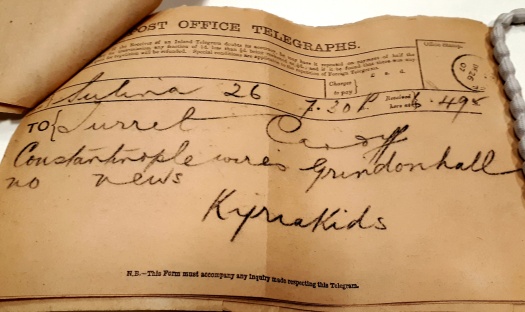

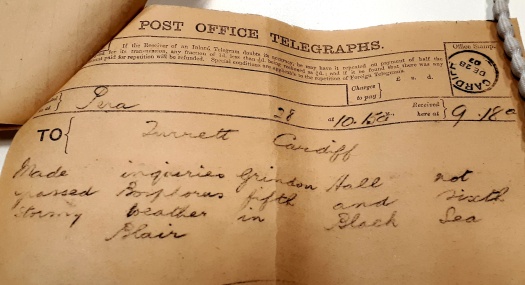

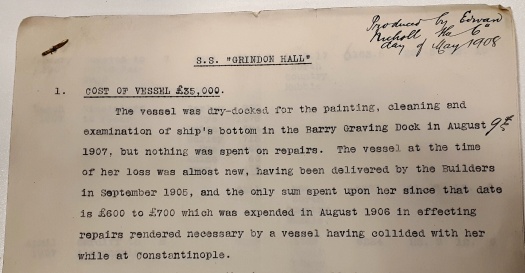

Inquiries concerning ships lost in mysterious circumstances obviously generated a greater amount of paper work since more possibilities had to be examined and more people questioned. In 1907 the SS Grindon Hall was supposed lost with all hands in the Black Sea when bound from Sulina in modern Romania to Glasgow. Only part of her lifeboat was ever found. Amongst the case papers for this particular inquiry are telegrams received from the master concerning the passage of the ship and copies of letters received by and from the master.

There are sad personal details of the master’s recent return to sea after his wife’s long illness, and his last letter reporting the final completion of loading after much trouble and delay which concluded …hoping we shall have a fine run home. Evidence seemed to indicate some instability after loading and in considering this, the court carefully examined plans of the ship, lists of repairs whilst in dry dock, a manifest of the cargo, and the testimony of former mates as to the ship’s sea-worthiness. The papers combine to supply a full and personal insight into the ship and her crew.

A common issue was the inability of crews to understand English. The Merchant Shipping Act of 1906 had attempted to address this problem by stipulating a requirement for sufficient knowledge of the English language to understand the necessary orders. However, a judge dismissed this stipulation as …futile and illusory… in 1908 when he investigated the stranding and loss of the SS Huddersfield of Cardiff off the coast of Devon. He had heard in the evidence how a Brazilian seaman was on look-out at night during heavy seas and failed to report any lights. The seaman’s knowledge of English was found to be so deficient that:

…he was not able to understand necessary orders nor to report intelligibly objects he saw. He had a wrong idea of the port and starboard sides of a vessel calling port starboard and starboard port.

At midnight he had handed over to a Greek seaman who had a similar lack of understanding of English for …he was not able to report broken water if he saw it. The case of the Huddersfield was again recalled in the inquiry concerning the loss of the SS Mark Lane of London off Spain in 1912. No inquiry of the Spanish look-out man’s English had been made before his engagement and he too showed total confusion between port and starboard.

The language barrier may also have been a factor in the tragedy which ensued after a collision in heavy fog between the SS Kate B. Jones of Cardiff, bound from Swansea to Catania in Sicily and SS Inveric of Glasgow. After the collision, the crew of the SS Kate had asked the Inveric to throw ropes but this was not done either because the request was not heard or the man on look-out did not understand. Worse still, the first and second officers proceeded immediately to abandon ship and board the Inveric. Left suddenly on his own, the master took the precaution of placing his wife and a Miss Yates of Chester in the starboard lifeboat along with three other members of the crew, whilst he examined the ship for damage. The lifeboat was lowered and suspended half-way and the rest of the crew crowded into the port lifeboat. When it was discovered that little water was entering the ship, the crew were recalled but the starboard lifeboat was found in the water towing by her stern tackle only, with the occupants nowhere to be seen. The court’s verdict on the sad events was sympathetic to the master but strongly censured the officers who abandoned ship:

The conduct of these two officers immediately after the collision was most culpable and without precedence in the history of British officers of the mercantile marine … such misconduct on the part of these two officers this court has no jurisdiction to punish except by exposure to the reprobation it deserves.

By the early 20th century over-insurance of ships had become a sinister and recurring theme. In 1910 what the Western Mail described as …the most important and sensational inquiry ever conducted in South Wales under the Merchant Shipping Act… was held after the loss of the SS British Standard of Cardiff off Negra Point in Brazil. Between July and August, a packed court listened in dismay to detailed testimonies of the crew which highlighted conflicting evidence and glaring discrepancies between the log and the master’s report of the mysterious sinking. It became clear that even if the sinking was not caused by human agency, the loss itself could have been averted had the master and chief engineer not been guilty of gross negligence.

The motive for the wilful sinking of the SS British Standard emerged as it was revealed that the promotion of the British Standard Steamship Company as a public company had not been a financial success. Paul Braun, the master of the vessel, the same Paul Brown who appeared on the company’s register of shareholders, had helped to finance the Company but had concealed the fact from the underwriters. His brother, the managing owner of the company, owed him £40,000. Most suspicious of all, the ship although valued only at £46,378 was insured for over £55,300. The Chief Engineer had insured his personal effects for the first time.

There were worrying implications for Cardiff itself. Great controversy ensued when it emerged that underwriters demanded higher insurance premiums for Cardiff-based ships as they were considered a bad risk. When the judge delivered his two and a half hour judgement, …the expectant hush which fell upon the crowded court reminded one of a great criminal trial. His observations outlined clearly the dangers of over-insurance:

Where a vessel is over-insured, one of the most powerful incentives for keeping her in good condition and seaworthiness is removed.

He called for legislation to prevent the abuse. The master was suspended for eighteen months and ordered to pay one thousand guineas towards the costs of the inquiry. The Chief Engineer was suspended for twelve months and ordered to contribute fifty guineas as costs. The third engineer was censured for misleading the court with false statements and for his conduct.

Unhappy reflections upon the outcome of inquiries and the relative impotence of the courts, often surface in the reports to the Board of Trade. The judge was not happy in the case of the SS Ouse of Cardiff, lost off the north coast of Devon in 1911, when no deposition was received from the man at the wheel at the time of the stranding since he had returned to sea. When the SS Powis of Cardiff was lost off Greece in 1907 …probably due to human agency, the judge in his report gave the opinion:

…wreck inquiries are of very doubtful utility. Owing to the conditions under which a vessel is lost or stranded, the absence of eye witnesses who are independent, the rare production of log books or other such valuable documentary evidence, the dispersing of the crew before an inquiry is held and the almost invariable absence of the most important witnesses… the court has but rarely the material to enable it to ascertain the whole truth.

Whatever the doubts of those participating at the time as to the usefulness of the shipping inquires, the records combine to provide a fascinating insight into the problems and hazards which beset merchant shipping in the past.